The first half of the interview was quite serious, the second half more light-hearted. The latter was published in the December issue of Rhythms as a 'quick-grab', but the first half remains unpublished. I've posted it here in full, along with the short intro from the published piece.

Alligator Records - Bruce Iglauer

|

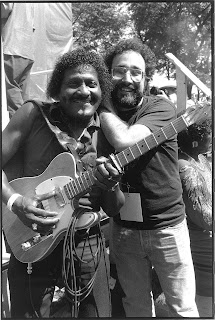

| Bruce Iglauer. Pic by Chris Monaghan. |

Four decades ago this year, a young Bruce Iglauer (disenchanted with the fact Delmark Records, where he worked, wouldn’t release an album by his favourite blues artist, Hound Dog Taylor) struck out on his own and made that record himself. Taylor became the first artist signed to Iglauer’s new label, Alligator, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Over the years, acts like Koko Taylor, Albert Collins and Johnny Winter have called Alligator home, as have countless others, and it’s been Iglauer’s effort and persistence that has seen a lot of these acts reintroduced to fans all over the world. This passion, dedication and pure love of the blues is why Alligator is here today, celebrating 40 years of genuine house rockin’ music, and why it always will be. Iglauer himself waxes lyrical on 40 years of blues.

Firstly, this year obviously marks 40 years since you first began Alligator – given all you’ve been through since then, how does that makes you feel today?

I’m constantly amazed that Alligator has survived (and sometimes even thrived) for all these years. However, I spend very little time thinking about the past or glorying in what we’ve done. My focus is always on the present and the future. Right now we’re preparing new releases by Joe Louis Walker, Janiva Magness, Lil’ Ed & The Blues Imperials (I’m producing that one), Curtis Salgado and Michael 'Iron Man' Burks (I’m producing that one too). So my focus is planning for next year, as well as dealing with the ever-more-difficult task of running a label in this ever-changing music business world. I never wanted to be a businessman, but it’s how I am able to record music I love and share it with the world.

Yr first project, the one which got the label off and running, was yr recording of Hound Dog Taylor back in 1971 – I believe the album was recorded in two days, straight to tape, mastered as you went. You then pressed 1000 copies and began distributing them from the trunk of yr car – tell me how you felt firstly, as you pulled out of Chicago with a boot full of those tapes, and secondly, how you felt when that record was first played on air, after you’d given it to a DJ.

In those days, I was making everything up as I went along, and spending every penny I had (a whopping $2500, which was the startup money for the label) to alert the world to Hound Dog Taylor. So we definitely mixed his album as we went, because that’s all I could afford! I remember the very first radio spin, at WGLD-FM in Chicago. It gave me a huge sense of fulfilment but also started my ‘addiction'. My music was on the radio!

|

| Iglauer and Albert Collins. |

Now I want more…more…more. So I drove to Detroit and got airplay on WABX and WRIF, and then on to Cleveland, and so on. I realised very quickly that Hound Dog’s music had something that spoke to others as it spoke to me. He knew how to put all that joy and raw energy and blues feeling into his music in a way that others could feel. I thought, 'Maybe I’ll be able to sell enough of this record to continue to record music I love'. And that’s pretty much been the story of my life since then; record music I love, and try to sell enough of it to continue recording even more music I love. By the way, I’m still in touch with those DJs who gave us our first spins.

You had some notable early successes – reintroducing the world to Koko Taylor, taking Albert Collins to the top, signing Johnny Winter… those must have been tremendously exciting times.

It’s always exciting both to help the recordings be created and to grow the audience for the artists. I only record artists whose music moves me, so every time an Alligator record gets a good review, is played on radio, or someone buys our music, it’s like a personal affirmation. But between 1971 and the late 1980s, I was producing or co-producing the vast majority of Alligator releases. I got to work with Hound Dog Taylor, Son Seals, Lonnie Brooks, Albert Collins, Johnny Winter, Roy Buchanan, Lonnie Mack, Koko Taylor, Lil’ Ed & The Blues Imperials, Professor Longhair, The Kinsey Report and many more.

I was often producing seven or eight albums a year. Because the market for blues was much bigger then, it seemed like almost every Alligator release was able to pay for itself and make a decent profit. So I was able to spend many, many days (and nights) in the studio. But as the years passed, we signed more artists who either came to us with their own finished master, or with their own producers, or were simply not appropriate for my producing skills. I’m a blues producer; I can help an artist make a great blues record. But my musical knowledge is limited, and I wouldn’t be much help in the studio with artists like Marcia Ball, JJ Grey & Mofro or Anders Osborne who are more 'roots' than blues artists.

Another thrill, then and now, is to be in the audience when my artists get an overwhelming audience response. I get caught up in the excitement — after all, I’m first and foremost a fan. I remember being in great audiences in Australia, seeing Hound Dog Taylor, Albert Collins and Lil’ Ed & The Blues Imperials. You guys know how to let it all hang out!

|

| Iglauer with Professor Longhair. |

It seems one of the reasons Alligator has survived, and prospered, for so long, it that it’s more of a ‘family’ as opposed to a ‘business’ – whether it’s the artists or the staff, it seems yr very close knit – how important has that been to you over the years?

I like to refer to all of us — myself, the artists, the staff — as 'The Alligator Family'. When I signed Joe Louis Walker recently, I sent an email welcoming him to the family. We tend to make long term commitments to our artists. If we believe in their talent and their professionalism, we will work hard to develop their careers, even if it takes a long time. Because we do more aggressive and concerted promotion and publicity than any other label in the blues or roots music world (and perhaps than any other label, period), we have become sort of the Rolls-Royce of labels for touring blues and roots artists.

We never stop working to make their careers more visible and their gigs more successful, even when they don’t have a new release. All the artists have my cell phone number, and before cell phones, they had my home number. And they know how to use it — if the van breaks down, the bass player quits, the club isn’t paying the amount on the contract or their girlfriend or boyfriend dumps them, they call Bruce, and Bruce answers and tries to help. To take it to an extreme, I had one artist live at my home for a month because he was trying to get away from his druggie friends and get clean. Others crashed at my house while on tour to save hotel costs. I’m never off duty. As a result, we often have earned intense loyalty from our artists. For example, Koko Taylor stayed with us for decades on a handshake. She said, “Bless the bridge that carried you across,” and she considered Alligator and me to be that bridge.

As far as the staff, I have the opposite attitude of a lot of businesses. I don’t think people are easily replaceable. When I have an employee who does his or her job well and is dedicated to Alligator and the artists, I’ll do everything I can to keep that person on staff. Alligator can’t pay as much as some other businesses, but we provide good health insurance, a retirement account, and if there is any significant profit at the end of the year, I’ll write bonus checks to the entire staff.

The result is that I have valuable people who have been with the company between 15 and 30 years. These are people I can trust to give 110% even when I’m not looking over their shoulders. Many of them have played a great role in Alligator’s success over the years (and rarely gotten credit). And I’m proud to say that in the 12 years since the worldwide implosion of music sales began (primarily because of illegal downloading), I’ve only laid off one person, and I gave him six months to find another job.

Obviously there would have been some highlights from the past 40 years – give me a few that really stand out in yr memory.

There are so many it’s hard to pick just a couple. Of course my first big thrill was making that very first Hound Dog Taylor record. Taking my favourite band into the studio, producing my first album, directing the mix (which, as I said, we did live; no chance to fix later) and realising that their music would translate from the live show onto record… it was literally a dream come true.

I’ve had huge thrills in the studio since, like when I brought Albert Collins, Johnny Copeland and the ‘new kid on the block’, Robert Cray, together for the Showdown! album and saw the record just about make itself, as each of these three very close friends inspired each other to greater and greater musical heights.

|

| Iglauer and Lonnie Mack. |

Then there was cutting the first album by Lil’ Ed & The Blues Imperials in three hours, when they had come into the studio to cut just two songs for an anthology and I enjoyed the music so much that I asked them to do, “a few more” (which turned into 30 recorded songs and a debut album). I had a great time making Lone Star Shootout album, another multi-artist session, this one with Lonnie Brooks, Long John Hunter and Phillip Walker. They had all been friendly competitors on the Beaumont/Port Arthur scene in Texas in the mid-1950s.

We cut some songs by their mutual heroes, like T-Bone Walker, Gatemouth Brown and Clarence 'Bon Ton' Garlow that brought back great memories for them. And when we had one more track to do late at night and everyone was tired, I woke up their senses of humour by mooning them through the glass of the control room. And I had no greater thrill than recording Crawfish Fiesta by another of my heroes, Professor Longhair, the Bach of Rock, in New Orleans. Dr. John was a huge help on that album. 'Fess declared it his favourite album ever, because he had never been given that level of artistic control. On the day we released it, he died suddenly at the age of 59. I guess he felt he had made his artistic statement. I was blessed to have worked with him. That’s the way I feel about most of my career. I’ve been blessed.

Of course I’ve also had great moments being in the audience and just watching my artists reach straight to the souls of the people around me. Seeing Albert Collins with his 150 foot cord walk through a line of Greek police (who were expecting a riot) and into a wildly appreciative audience, for example. Or seeing Shemekia Copeland’s super successful debut at the Chicago Blues Festival right after we released her debut album. And then there was my honeymoon party at Buddy Guy’s Legends club in Chicago, where musicians from all over the country flew in to play for my wife and me (and about 400 of our closest personal friends). That night, Luther Allison and Koko Taylor performed together; I think it was the only time they ever did. And now they are both part of the Great Blues Band in the Sky.

And no doubt some low-lights – hit me with a couple of those.

As you can imagine, having started at 23 with my first artist being 55, I spent the first part of my career dealing with a lot of death. Since I began, I’ve lost good friends who were also key artists — Son Seals, Koko Taylor, Hound Dog Taylor, William Clarke and so many more. Being a professional blues musician is very hard, and blues men and women tend to die younger than they should. Many of them come from very hard backgrounds — poverty, poor health care, physical labor jobs, and of course my black artists have had to deal with racism. These things age people prematurely. So I’ve buried a lot of people I cared about.

I’ve had great frustration with some artists whom I thought were great and the public never totally embraced. like Fenton Robinson, C.J. Chenier, Michael Hill’s Blues Mob, Rusty Zinn, Long John Hunter and more.

"I’ve also managed to not sign artists whom I should have signed, like a guy I dismissed as, “the loudest Albert King imitator I ever heard”, named Stevie Ray Vaughan. And that’s not my only mis-step!"

And also some possible hair-raising moments – the bio on the label website mentions you’ve gotten more than a few of yr artists “out of some rather sticky situations”… care to elaborate?

I can think of a lot of them. The most obvious one was when I was in a train wreck in Norway in 1978 with the entire Son Seals Band. Because we had derailed and skidded down a steep embankment and part way into a fjord, no one could get to our train car. The band and I had to rescue all the passengers before the train car slid further into the water. During the wreck the drummer, Tony Gooden, was injured so badly that he never played again. It was the most harrowing night of my life. That night the artists and I got each other out of a very sticky situation.

|

| Iglauer with Mavis Staples |

One time I was on the way to a gig in the suburbs with Hound Dog Taylor. We were caravanning two cars and he was pulled over by the police. I stopped of course. In the process of ‘negotiating’ with the cops, I ended up being arrested, spending one night in jail on the South Side of Chicago followed by two years on probation for, “interfering with an officer in the performance of his duty,” and couldn’t leave the county without permission of my probation officer.

On my 60th birthday, I celebrated by spending 14 hours at Cook County Jail trying to bail out a musician member of the family who was arrested on a bogus charge. It took from 9am to 11pm to get him out.

On a couple of occasions, it was the artists who got me out of sticky situations. Brewer Phillips, who played with Hound Dog Taylor, twice helped me deal with people who were coming at me with knives. One was a discontented musician whom I had recorded for an anthology but didn’t sign for a full album. The other was a concert promoter who was refusing to pay the band and the discussion became somewhat, um, heated. In both cases, I was unscathed thanks to quick action by Brewer.

40 years in, and Alligator is still going strong; in fact, you’d have to be the premier indie blues label in the world. Can you ever see an end to this? What are yr plans for the future? Another 40 years?

An end to this? Well, I suppose I’ll die someday, but I intend to keep doing this as long as I can. I’d like to die at either a great gig or in the studio listening to one of my favourite artists cut a terrific performance. But I can sure imagine doing this for another 40 years.

Alligator Records 40th Anniversary Collection is available now through Alligator Records / Only Blues Music.

Alligator Records 40th Anniversary Collection is available now through Alligator Records / Only Blues Music.